Let’s be honest: I didn’t consider British food a culinary marvel. Quite the opposite. It was more famous for being bland, dry, tasteless and, quite frankly, very unoriginal. Even the national pride, fish and chips, doesn’t have pure-bred British origins. The fried fish came with Sephardic Jewish immigrants from Spain and Portugal, while the “chips” part took shape in Northern England, also with disputed roots. Britishness lies in the combination of these two items into one fast-food dish and the addition of soggy mushy peas. Not exactly a kitchen jewel.

When I arrived in England, I didn’t have high expectations — especially coming from my previous destination, where I had served an aristocratic British family in Northern Ireland. That experience taught me to cook with a bit of herbs and absolutely no salt.

“Salt is bad for you,” I was reminded almost every day, reinforcing the stereotype I’d always heard.

Then One Saturday Evening

However, I soon realised not all was lost in the English kitchen.

One Saturday evening, starving after a long day exploring an English heritage castle in Staffordshire, we stopped at a Crown Carveries. What a discovery.

I opened the door, and the smell rolled out before anything else could — thick, hot and unapologetic, pulling you inside and refusing to let go.

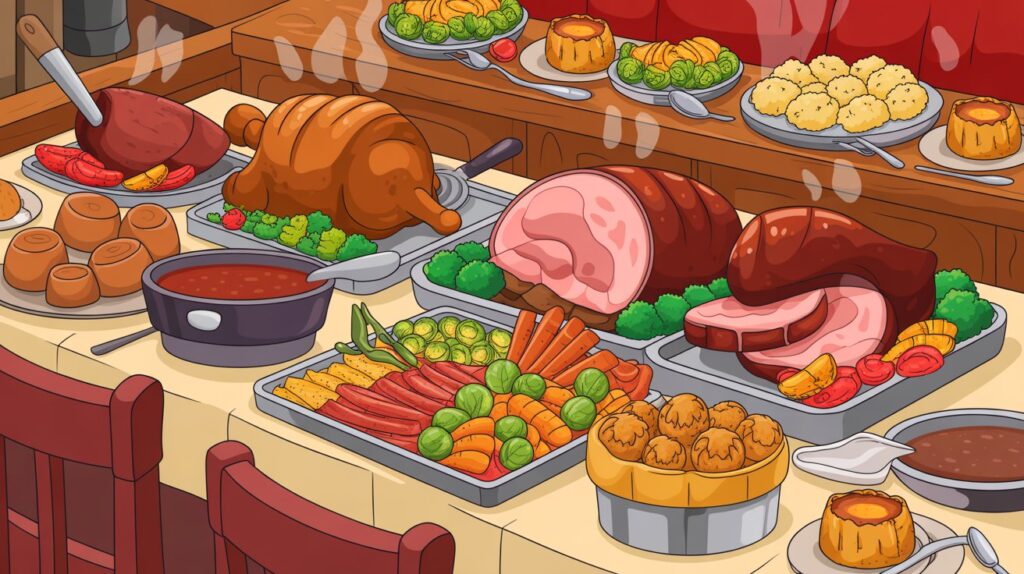

It was roast meat first: dark, blistered edges of beef giving off that deep, savoury scent of fat and heat; pork smelling rich and indulgent, all crackling and salt; lamb carrying a softer, almost sweet warmth, threaded with rosemary. The air felt heavy with it, as if it could settle on your clothes.

Then came the gravy — peppery, glossy, unmistakably meaty. It smelled brown and slow-cooked, as bones, onions and patience melted into liquid. You could almost taste it already, clinging to the back of your tongue.

Beneath that, the vegetables breathed out their sweetness: carrots and parsnips caramelising at the edges, potatoes crisp and buttery, steaming softly, promising that first crunch before the fluff inside. There was butter in the air. Salt. A faint herbal note that reminded you this was food made to be shared, not rushed.

The smell didn’t ask politely. It claimed the space and wrapped itself around my hunger.

The Queue

Being told that you get a slice of meat and then help yourself to the spuds and veg sent my stomach growling in agreement, rushing me into the never-ending line of people standing behind each other like soldier ants.

Can the line move faster?

I painfully counted every person ahead of me, waiting for my turn. This felt unnecessary — and extremely cruel.

If my porcelain plate had been flexible enough to bend under the weight, it would have turned into a bowl.

The selection was immense. Every step along the buffet brought another impossible decision, so I did what everyone else seemed to be doing: a bit of everything. Beef, turkey, pork, gammon, followed by a generous spread of vegetables… and a massive Yorkshire pudding drowned in gravy. I knew I was going to die before taking my first bite.

Delicious. Sooo delicious it hurt my stomach.

As I scoffed my way through the plate, bite by bite, I felt my jeans shrinking with every mouthful. I unbuttoned one button, then the other — purely to prevent bodily harm to myself or others should a button lose patience and shoot through the air to an unknown destination.

Things Escalated

A carvery doesn’t just force you to eat until you can’t breathe; it also makes you remove whatever stands in the way of your stomach expanding.

Sweatpants. Next time, wear sweatpants.

I made a mental note on this educational journey.

To cut the story short, we waddled out penguin-style, swaying from side to side, slightly afraid that all the food might start pouring out of our belly buttons if that were humanly possible.

You might wonder why we didn’t just leave food on our plates once we felt full. If you have to ask, then you clearly didn’t grow up with the sentence:

“You must eat everything on your plate. Children on the other side of the world are starving.”

The place became our favourite Sunday destination — until we discovered Toby Carvery. Holy moly. Not only did the carvery bring us to our knees, but the warm chocolate fudge cake with ice cream finished us off completely. Glossy on top, hiding a rich, moist interior that melted in your mouth, the hot fudge collided with ice cream in a way that felt dangerously close to dessert nirvana.

Toby Carvery

British food was never dry or bland again. As for portion control, we never learned it. We kept getting stuffed until our two children were born, and gradually helped us offload our plates. What I did learn, however, was not to wear tight clothes — purely as a precaution.

Once we left England, of all the things I left behind, this one stayed with me. And I’m fairly certain that when I return one day, I’ll head straight to Toby Carvery in Stoke-on-Trent — where I was served a life lesson proving that British food wears its culinary crown on a carvery.

If you think asking a simple question is harmless, try doing it in a Tunisian market. From accidental negotiations to cultural landmines you never saw coming, Life in Translation is a collection of moments where language, logic, and dignity quietly fall apart.